Most product purchase decisions are made directly at shelf and are made non-consciously. Packaging therefore has a critical role to play in influencing product perceptions and in-store purchase decisions, especially for food products, where purchase decisions are characterised by low-involvement processes. This is also the case for online shopping, where a passive state of attention dominates. With the growth of e-commerce, understanding these non-conscious processes has become increasingly more important.

Given most of these decisions are below conscious awareness, assessing packaging effectiveness using traditional research methods often fails to capture the rapid-fire reality of people’s shopping decisions.

How does marketing work?

First: how does marketing actually work? Although it has been around for over 100 years, the AIDA (Attention -> Interest -> Desire -> Action) model is still the most widespread framework used by advertisers, and understandably so. There are a number of similar models that follow the same simple sequence of cognition -> emotion -> behavior: a clear and easy way to summarise the complexity of people. We hear a message; we process it with the ‘thinking’ part of our brain; the ‘emotional’ part then kicks in; and finally action is or is not triggered. Or in other words, we ‘Think’, ‘Feel’ and ‘Do’.

Except that this is not how we process information, nor is it how the brain works. The reality is more complex, with feed-forward and feed-back processes, simultaneous activation of different brain areas, and conscious and nonconscious awareness.

Bottom-up vs top-down attention

In order to be consistent with modern psychology and neuroscience, we need to accept that communication operates across a spectrum of responses, both explicitly and implicitly.

Most of our supermarket trips can be characterised by routine purchases, shopping on autopilot and letting our low involvement processing do all the heavy lifting, while our effortful, ‘hard’ thinking goes on holiday. When it comes to attention, we need to consider both bottom-up and top-down attentional processes.

Bottom-up attention is a rapid, automatic form of selective attention, driven by external factors or physical properties of stimuli, such as colour or intensity. It is also known as saliency-based attention, indicating that the more salient an object, the higher the probability of it being noticed. Humans use mental shortcuts to piece together visual information to create a scene, and therefore don’t see all the smaller details – only what is salient.

Top-down attention refers to internal guidance of attention based on prior knowledge, voluntary plans, and current goals. It is often compared to a spotlight, which enhances the processing of the selected item.

The figure above gives an example of bottom-up and top-down attention in action. Processing the top square we either see it as a 13 or a B (bottom-up attention processes only what is there), however when we see it in context with other numbers or letters, this alters what we see (our top down attention modulates our bottom-up attention).

Key brand assets

The human brain is wired to see structure and patterns: it helps us make sense of the world. We use shortcuts to piece together visual information to create a scene and therefore do not see all the smaller details, only what is salient.

Past research has shown that consumers rely on well-known brand names because these brands simplify choice, promise a particular level of quality, reduce risk, and engender trust. Brands are essentially shortcuts, and key brand assets are shortcuts to brands. They include: colours, slogans, sounds or shapes such as McDonald’s’ Golden Arches and Guinness’ harp (read more about brand assets here). Achieving the required level of distinctiveness and saliency requires reinforcement and refreshment over time.

Findability

To avoid a Tropicana-style disaster (where a redesign of a familiar pack resulted in one significantly less familiar and that suffered a drop in sales), packaging redesign has to be done in a way that is new enough to be salient, but familiar enough to be recognisable. This is based on Weber's Law, which states that an additional level of stimuli known as the ‘ Just Noticeable Difference’ is necessary for the majority of people to perceive that there is, in fact, a difference between the resulting stimulus and the initial stimulus.

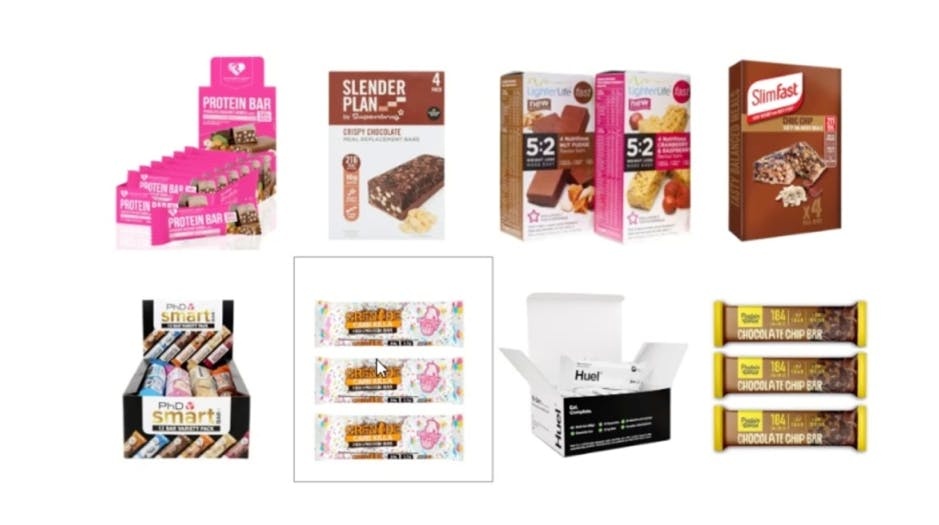

In research I conducted for HeyHuman for the brand SlimFast, we tasked participants with finding the various SlimFast pack design options amongst other competitor products using a Reactor Findability test. We then compared the time it took to find the old SlimFast packaging versus the new, refreshed packaging. We found that the old pack design was quicker to find than new pack design, across both users and non-users. However, a slight difference was to be expected, as the old pack would already be encoded into people’s memory and therefore would be more mentally available, aiding the search process. Huel was the only competitor that matched SlimFast’s findability. Given the size of Huel’s brand name and the saliency of its emboldened, black on white packaging, as well as its distinction against the other brands, this was no surprise. Using Findability tests (as included in our Pack Reactor solution) we can minimise the risk of a pack being launched with significantly weaker Findability than the existing current product.

Visual Attention

We also typically test the visual attention power of pack designs as part of our assessment. Here the aim is to see how well the packaging stands out and assess its visual impact. Therefore, we used a mixture of eye-tracking and visual saliency testing.

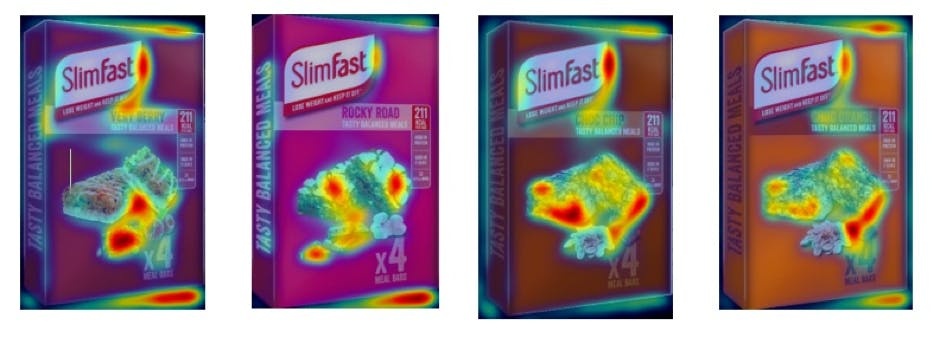

Eye-tracking records people’s precise eye movements to see what is noticed and what is ignored. It provides metrics such as time to first fixation and time spent on stimulus, which give us an indication of both bottom-up and top-down visual attention. Visual saliency testing predicts visual attention to understand which elements in a visual scene are most salient in terms of bottom-up visual attention.

The output of both these methods results in a heatmap, where the gradient of colour from cold to hot reflects the time spent looking at that part of the image from short to long (e.g. red representing the longer ‘hotspots’ of visual attention).

For the SlimFast pack research, it enabled us to compare the saliency of each flavour variant, revealing findings such as which flavour variant hue detracts from the key brand assets. Allowing us to provide more fine-grained feedback on each design.

Emotional response

Emotion dictates much of our decision making, even if it is below our conscious awareness. We have access to these subconscious or implicit emotions by using neuroscience research methods.

For the SlimFast packaging research, we wanted to see if the new packaging generated more implicit motivation than the old packaging. In this case we used the Implicit testing.

Implicit testing requires the person to categorise two concepts with an attribute, as quickly as they possibly can: the quicker the respondent pairs the concept and attribute, the stronger the internal association. These associations are known as ‘Implicit Attitudes’, and research suggests they influence many cognitive processes such as memory, perception and choice. To access people’s personal motivation toward the product, we used the attributes ‘For me’ and ‘Not for me’ in relation to each design. The results showed that people viewed the new packaging as more motivating than the old version. This was extremely useful information that enabled the recommendation of moving forward with the new design.

Now more than ever, gauging customer sentiment and motivation is incredibly difficult. However, it is vital for any brand to thrive. Neuroscience has given our clients the tools to make decisions they just could not make before. These non-consious attentional and emotional forces that drive consumer choice are vital to understand.

.jpg)